Anyone who denies the law of non-contradiction should be beaten and burned until he admits that to be beaten is not the same as not to be beaten, and to be burned is not the same as not to be burned.

– Avicenna, Persian polymath of the 10th-11th centuries

The law of non-contradiction is (at least I hope) self-explanatory. Claims that contradict one another cannot both be true at the same time in the same sense. This means that either theism or atheism is correct, but both cannot be true because they make contradictory claims about the existence of God. This law or principle is generally an easy one to accept, which is why Avicenna’s proposed reeducation regimen for those who deny the law of noncontradiction would rarely be put into use even if it were to be adopted.

A concept that is closely related to the law of noncontradiction is the law or principle of excluded middle. On this point, let’s take a look at Aristotle:

But on the other hand there cannot be an intermediate between contradictories, but of one subject we must either affirm or deny any one predicate. This is clear, in the first place, if we define what the true and the false are. To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true; so that he who says of anything that it is, or that it is not, will say either what is true or what is false

As an example, either God exists or He does not. Either Jesus rose from the dead or he did not. Pick any other example you like, but the rule is the same: there are no third options.

David Hume, by Allan Ramsay (Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

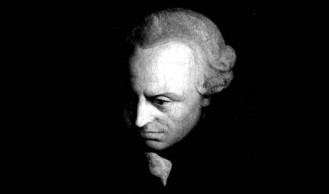

Most of us have no real issue with either of these laws of thought and readily accept them. Two influential philosophers, however, have staked out positions that require denying these basic laws of thought. Both David Hume and Immanuel Kant played important roles in developing the modern philosophies upon which many non-theists now rely.

Hume’s basic idea was what we might refer to today as logical empiricism or positivism. To Hume: “All objects of human reason or enquiry may naturally be divided into two kinds, to wit, Relations of Ideas and Matters of Fact.” In other words, all meaningful ideas are either true by definition (“Though there never were a circle or triangle in nature, the truths demonstrated by Euclid would for ever retain their certainty and evidence.”) or they must be based on sense experiences (“What is the nature of that evidence which assures us of any real existence and matter of fact, beyond the present testimony of our senses, or the records of our memory?). Thus, Hume rules out the metaphysical as a source of knowledge, i.e., no truths about God can ever be established. Hume concludes his Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding with this:

If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.

Hume’s work forms part of the train of thought leading the way toward what might now be known as the verifiability principle: “a statement is meaningful only if it is either empirically verifiable or else tautological.”

One might pause to ask, however, “Is the verifiability principle true by definition? Can the verifiability principle be confirmed by empirical observation?” The answer to both questions, I think, is obvious: no, it is neither true by definition nor can it be confirmed by empirical observation. Perhaps, then, Hume might have done well to reconsider where we ought to commit works that do not contain any experimental reasoning. Hume tries to prove too much and in so doing saws off the branch he is sitting on.